calsfoundation@cals.org

White River

The 722-mile-long White River flowing through northern Arkansas and southern Missouri is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. The river begins in northwestern Arkansas in the Boston Mountains and flows northwest toward the Fayetteville (Washington County) area, where it then turns north. Near Eureka Springs (Carroll County), the river enters Missouri. It then flows southeast back into Arkansas past Bull Shoals (Marion County), Mountain Home (Baxter County), and Calico Rock (Izard County). At Batesville (Independence County) begins the second section of the river, known as the lower White. From Batesville, the White River flows south for 295 miles through Arkansas’s Delta region, past Augusta (Woodruff County), Des Arc (Prairie County), Clarendon (Monroe County), and St. Charles (Arkansas County), before emptying into the Mississippi River in Desha County.

Thousands of years before European contact, various Native American groups lived along the White River. Large agricultural towns of the mound-building Mississippian culture were present along the lower White until at least the expedition of Hernando de Soto in 1541–42. Delaware and Shawnee settlements were established in the upper White River valley in the 1780s with Spanish encouragement. French hunters and trappers were present in the White River area during the eighteenth century. In 1819, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft explored the river and commented on its diverse scenery and the suitability of its clear, white waters for boating.

Keelboats were an early mode of transportation for Arkansas’s early settlers. Above Newport, sharp bends, rapids, and low water levels along the river during the summer months—as well as the additional manpower required to move keelboats upriver against the current—generally allowed travel only downriver. The lower White was navigable in both directions from the Mississippi River to Newport. The river served as a highway carrying supplies and crops back and forth from the frontier settlements to river towns such as Memphis, Tennessee, and New Orleans, Louisiana. Steamboat travel on the upper White began in 1831, and towns along the upper White in Arkansas and Missouri continued to dredge and clear the river for steamboat traffic until at least the early twentieth century. After the Civil War, steamboats were gradually replaced by railroads.

The river’s meandering course lends itself to a variety of environments—from the seasonal, fast-flowing headwaters of the upper White to the wide, slower-moving stretches farther down the river. Between these two extremes are a variety of smaller streams and lakes that provide excellent habitats for trout fishing. Other species, such as bass and catfish, are also present at various locations along the river. Important tributaries of the upper White include the Buffalo National River and Little Red River. Tributaries of the lower White include the Black and Cache rivers. Many of these smaller tributaries have their own recreational and wildlife protection areas maintained under the supervision of various departments at both the state and federal levels. During the Flood of 1927, the White flooded below Batesville, and areas to the north and east in Randolph, Clay, and Lawrence counties were also flooded by the White River’s tributaries. Torrents from the Mississippi River even caused the White to run backward at one point.

In 1935, the White River National Wildlife Refuge was established under the supervision of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for the protection of migratory bird species. The 160,000-acre sanctuary is one of the largest remaining bottomland hardwood forests in the Mississippi River Valley.

Four major dams in Arkansas and one in Missouri, all constructed by the 1960s along the upper river and its tributaries, create manmade lakes and generate hydroelectric power for the region. Numerous state parks and wildlife reserves are associated with these areas. Some of these lakes include Beaver Lake, Table Rock Lake (in Missouri), Bull Shoals Lake, Norfork Lake, and Greers Ferry Lake.

Usage of the lower White has been more intensely agricultural and commercial than the upper White. As rice cultivation in eastern Arkansas has grown, it has steadily depleted the shallow water aquifer of Arkansas’s Grand Prairie. The Grand Prairie Irrigation Project—supported by the Arkansas Soil and Water Conservation Commission, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and some farmers—seeks to pump water directly from the White River via a system of ditches, pipes, and canals in order to irrigate farms in the area. This project has met resistance from conservationists and some farmers, who assert that the project will lower the water level of the river and that there are more sustainable, less expensive alternatives to the $319 million project. As of 2008, the last of the irrigation pumps is waiting to be installed pending the resolution of litigation.

The impact of barge navigation on the lower White also remains a contentious issue. Currently, a 250-mile-long, eight-foot-deep channel facilitates barge traffic from the Mississippi River to Newport. Despite a modest amount of barge traffic, the Lower White River Improvement Project, promoted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and various barging interests, seeks to deepen this channel by an additional foot to bring the lower White’s navigational capacity up to standard with other large rivers. This plan is opposed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Arkansas Wildlife Federation, and various other groups. Although the Corps of Engineers believes that the project can be completed in an environmentally responsible way, opponents of the measure believe that deepening the channel will harm the delicate wetland ecosystem of the lower river and damage the economies of towns like Stuttgart (Arkansas County), which depend upon the biodiversity of the floodplain for tourism and hunting. Funding for this measure has consistently been defeated at the state and federal level, but a study was initiated in 1996 to examine the feasibility of deepening the river via the use of more than 100 wing dikes at thirty locations along the river. The project is still in limbo pending appropriate funding.

In recognition of local conservation efforts and to encourage governmental support of those efforts, the federal government in 2013 named the White River a National Blueway—the second such designation in the country. However, due to public backlash, the U.S. Department of the Interior dropped the White River from the National Blueway program later that year.

For additional information:

Browne, Turner. The Last River: Life along Arkansas’s Lower White. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

Helmer, Joel William. “Float Trips, Dams, and Tailwater Trout: An Environmental History of the White River of Northern Arkansas, 1870–2004.” PhD diss., Oklahoma State University, 2005.

Huddleston, Duane, Sammie Cantrell Rose, and Pat Wood. Steamboats and Ferries on the White River: A Heritage Revisited. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

Martin, Rick. “In the Lap of the Brown God: A White River Journey.” Arkansas Times, August 1982, pp. 36–46, 48–51.

Nelson, Rex. “Follow the Flow.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 18, 2020, pp. 1H, 6H.

Ogilvie, Craig. “White River’s Navigation Dams: Relics from the Steamboat Era.” Ozarks Mountaineer (May/June 2008): 15–20.

Pfeifler, Anna Ruth. “River of Conflict: The White River during the Civil War.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2010.

White River National Wildlife Refuge. http://www.fws.gov/whiteriver/ (accessed April 26, 2022).

Aaron W. Rogers

Conway, Arkansas

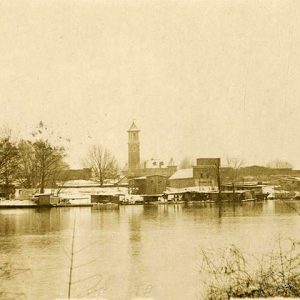

Batesville 1915 Flood

Batesville 1915 Flood  Beaver Boat Launch

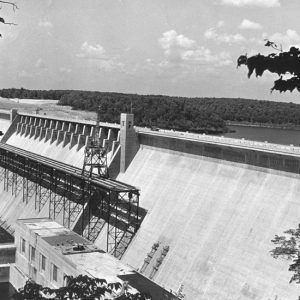

Beaver Boat Launch  Beaver Dam and Lake

Beaver Dam and Lake  Black and White Confluence

Black and White Confluence  Bull Shoals Dam

Bull Shoals Dam  Bull Shoals Dam

Bull Shoals Dam  Bull Shoals-White River State Park

Bull Shoals-White River State Park  Clarendon Access

Clarendon Access  Clarendon Bridge

Clarendon Bridge  Clarendon Riverfront

Clarendon Riverfront  Cotter Ferry; 1904

Cotter Ferry; 1904  Des Arc Bridge

Des Arc Bridge  Des Arc Park

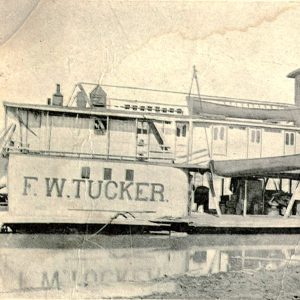

Des Arc Park  F. W. Tucker Steamboat

F. W. Tucker Steamboat  Fish Market

Fish Market  Georgetown River Access

Georgetown River Access  Hess/O'Neal Ferry

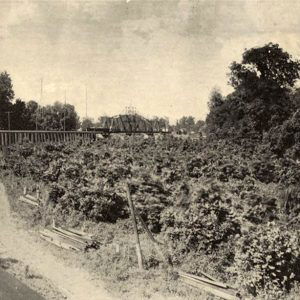

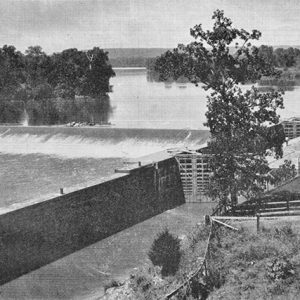

Hess/O'Neal Ferry  Lock and Dam Number 1

Lock and Dam Number 1  Lock and Dam Number 1

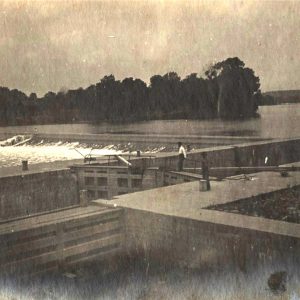

Lock and Dam Number 1  Lock and Dam Number 2

Lock and Dam Number 2  Harry Miller

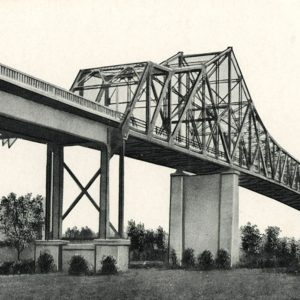

Harry Miller  Newport Bridge

Newport Bridge  Oil Trough Park

Oil Trough Park  Pearling Industry Barges

Pearling Industry Barges  Penters Bluff

Penters Bluff  Ramsey's Ferry

Ramsey's Ferry  Rim Shoals

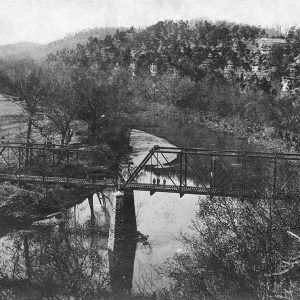

Rim Shoals  Rogers Bridge

Rogers Bridge  Snag Boats on White River

Snag Boats on White River  St. Charles Access

St. Charles Access  St. Charles Ferry

St. Charles Ferry  Steamboats Illustration

Steamboats Illustration  White River

White River  White River at DeValls Bluff

White River at DeValls Bluff  White River

White River  White River

White River  White River Access

White River Access  White River at Georgetown

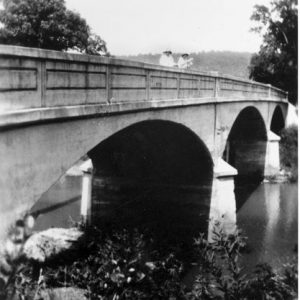

White River at Georgetown  White River Bridge

White River Bridge  White River Bridge at Elkins

White River Bridge at Elkins  White River Dredge

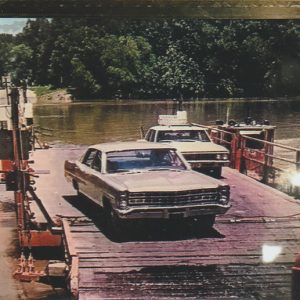

White River Dredge  White River Ferry

White River Ferry  White River Ferry

White River Ferry  White River Fishing

White River Fishing  White River Flooded

White River Flooded  White River in Stone County

White River in Stone County  White River Monster Refuge

White River Monster Refuge  White River Scene

White River Scene

This entry has no mention of the aborted lock and dam system of the early 1900s. Three of a projected ten locks and dams were completed, before the project was canceled. #1 at Batesville and #2 a few miles upstream have been heavily modified for hydropower production. #3, below Penter’s Bluff, is intact, as it wasn’t suitable for the hydro installation. It is nearly inaccessible, but can be visited with a good map and the right vehicle.